In its first weeks on Mars, NASA’s Perseverance rover has captured dazzling highlights, from video of its own dramatic landing to the first audio recordings from the red planet, the sounds of wind blowing and the rover’s laser zapping rocks.

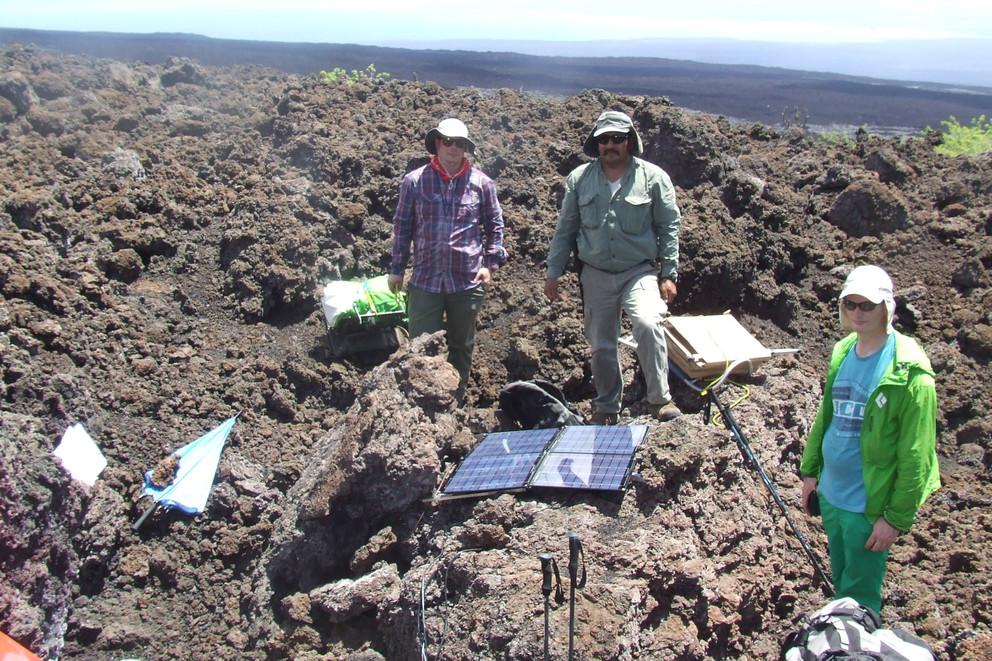

Hours before the 2018 eruption of Sierra Negra, the Galápagos Islands’ largest volcano, an earthquake rumbled and raised the ground more than 6 feet in an instant. The event, which triggered the eruption, was captured in rare detail by an international team of scientists, who said it offers new insights into one of the world’s most active volcanoes.

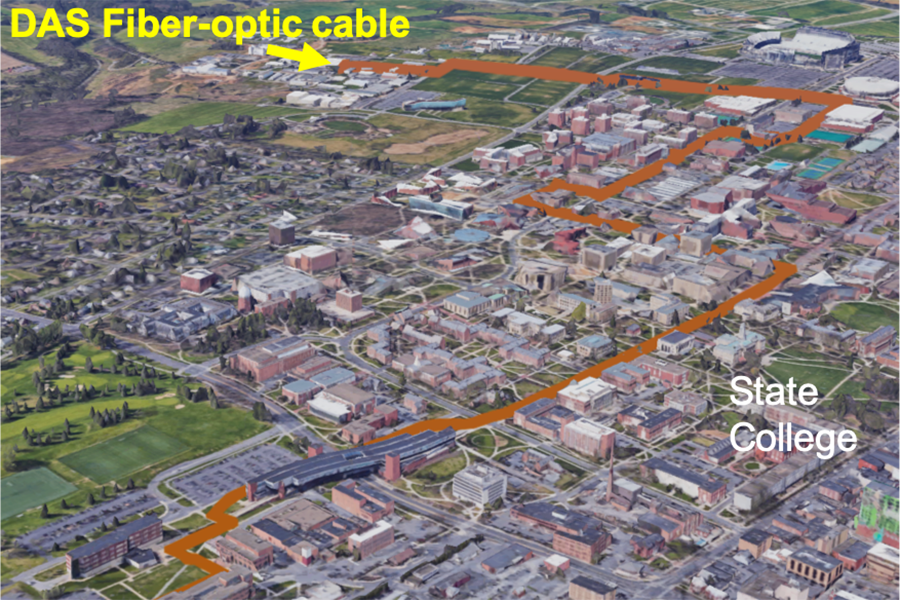

Fiber-optic cables run underneath nearly all city grids across the United States and provide internet and cable TV to millions, but what if those systems could also provide valuable information related to hazardous events such as earthquakes and flooding? A team of researchers at Penn State have found they can do just that.

Landslides caused by the collapse of unstable volcanoes are one of the major dangers of volcanic eruptions. A method to detect long-term movements of these mountains using satellite images could help identify previously overlooked instability at some volcanoes, according to Penn State scientists.

Jesse Reimink remembers the first time someone planted the Earth science seed that for him blossomed into a career in the geosciences.

Nearly two decades ago, Reimink was a high school student of Chris Bolhuis, a nationally recognized teacher with a passion for promoting Earth science education. Reimink, now an assistant professor of geosciences at Penn State, said Bolhuis gave him that sense of wonderment about the world we live in and it inspired him to both teach and conduct research.

No other glacier has received as much attention in recent years from the scientific community as West Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier. The glacier sits mostly on land, which means that melt from the glacier will cause sea levels to rise. Sridhar Anandakrishnan, professor of geosciences at Penn State, will give an overview of Thwaites Glacier and discuss the prospects for sea-level rise from this and similar glaciers at 11:15 a.m. Wednesday, Jan. 27. The talk will be broadcast via Zoom.

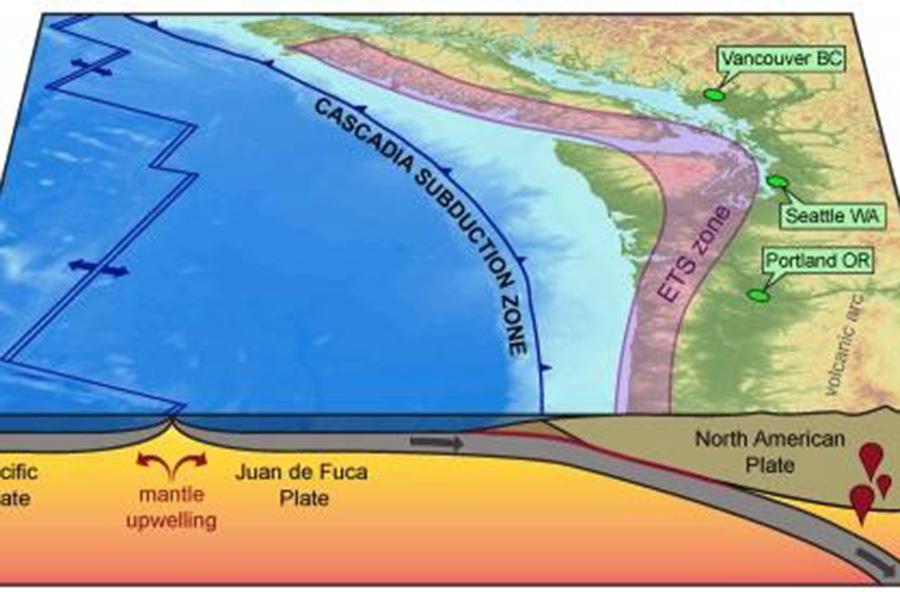

Megathrust earthquakes and subsequent tsunamis that originate in subduction zones like Cascadia — Vancouver Island, Canada, to northern California — are some of the most severe natural disasters in the world. Now a team of geoscientists thinks the key to understanding some of these destructive events may lie in the deep, gradual slow-slip behaviors beneath the subduction zones. This information might help in planning for future earthquakes in the area.

The asteroid impact 66 million years ago that ushered in a mass extinction and ended the dinosaurs also killed off many of the plants that they relied on for food. Fossil leaf assemblages from Patagonia, Argentina, suggest that vegetation in South America suffered great losses but rebounded quickly, according to an international team of researchers.

Tucked into the rolling hills of Stone Valley, Cole Farm seems like a typical central Pennsylvania farm. A gravel driveway slopes down to a steel and wood-plank bridge that spans Shaver’s Creek. The path continues relatively flat, past a murky green retention pond and two barns, to a log farmhouse nestled at the base of a hill. A spring trickles through the wooded swale west of the house. Sloping fields are flush with alfalfa, corn, hay grass, and wheat.

Geoscientists have long known that some parts of the continents formed in the Earth’s deep past, but the speed in which land rose above global seas — and the exact shapes that land masses formed — have so far eluded experts.