Kimberly Lau, assistant professor of geosciences and an associate in Penn State’s Earth and Environmental Systems Institute, received the Pre-tenure Excellence Award from the Geobiology and Geomicrobiology Division of the Geological Society of America. The award recognizes Lau’s accomplishments in the fields of research, mentoring, service and leadership in the geobiology and geomicrobiology community.

Fires in semi-arid forests in the western United States tended to burn periodically and at low severity until the policy of fire suppression put an end to these low-intensity events and created the conditions for the destructive fires seen today. Understanding the benefits of these periodic fires and the forest structure that they maintained may help land managers and communities avert megafires in the future, according to researchers.

Timothy S. White, research professor in Penn State’s Earth and Environmental Systems Institute, was elected a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. White is one of 50 newly elected Fellows receiving the honor in recognition of their sustained records of distinguished contributions to the geosciences and the Geological Society of America.

Machine learning techniques may help scientists better understand the intricate chemistry of streams and monitor broader environmental conditions, according to a team of researchers.

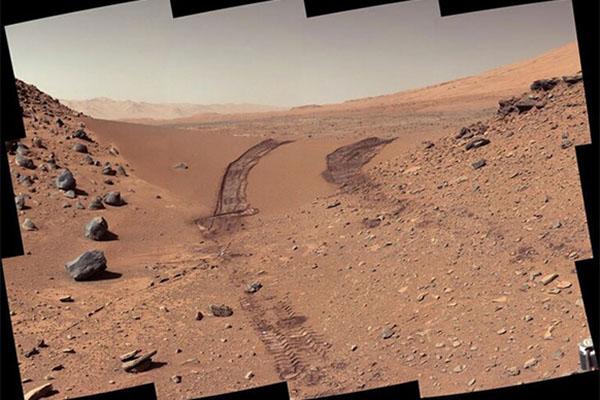

A combination of a once-debunked 19th-century identification of a water-carrying iron mineral and the fact that these rocks are extremely common on Earth, suggests the existence of a substantial water reservoir on Mars, according to a team of geoscientists.

Every year the GBGM executive committee selects exceptional scholars to receive awards for their accomplishments in research, education/mentoring, and service in geobiology.

Alan Taylor, professor of geography and ecology, will serve as interim director of the Penn State Earth and Environmental Systems Institute (EESI) while director Susan Brantley is on sabbatical. His appointment began July 1.

Jennifer Macalady, professor of geosciences, has been appointed director of Penn State’s Ecology Institute, effective July 1. She holds an appointment in the Department of Geosciences in Penn State’s College of Earth and Mineral Sciences.

In March 2020, daily life in the United States changed in an instant as the country locked down to deal with the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. New research reveals how residents in one community returned to their routines as the restrictions lifted, according to a team of Penn State scientists.

Over the last decade, geothermal energy has progressed throughout the world as an environmentally friendly, sustainable source of energy. Using the heat from the Earth’s crust, geothermal power plants harvest and store energy in massive underground reservoirs carved out of stone. Once built, the reservoirs are inaccessible and monitored remotely — but not infallible. Earthquakes and more can fracture the subsurface rock, risking the integrity of the reservoir and endangering energy production.